Cookie-Click Showdown: Why ClickHouse Crushes Redis at Scale

- LK Rajat

- Jun 19, 2025

- 8 min read

I built a “cookie-clicker” backend where each click increases your count and updates a live top-10 leaderboard. With 200 clients clicking continuously for 30 seconds, Redis (updating and broadcasting on every click) handled about 9,950 requests per second (95% of requests completed in roughly 26.8 ms). ClickHouse, which groups 50 ms of clicks into one write and refreshes the leaderboard every 250 ms, managed around 16,390 requests per second (95% completed in about 15 ms).In short: if you want truly instant updates at a modest scale, Redis (≈ 10k req/sec) works well. If you expect tens of thousands of clicks per second and can accept a 50–250 ms leaderboard delay, ClickHouse is faster.

Check out the full source code on GitHub: https://github.com/rajatmohan22/cookie-clicker

The Challenge in Plain English

Imagine a browser game where every time you click a big “🍪 HIT ME!” button, your browser does:

POST http://localhost:8080/hit { "user": "alice" }The server must:

Count your click—so it knows how many clicks “alice” has total.

Broadcast an updated top-10 scoreboard to all connected players (using WebSocket).

For a handful of players, any approach works. When hundreds of players click dozens of times per second, you need a very efficient system. We compared two main strategies:

Redis Approach

With Redis, each click is handled immediately and individually. The general flow for every incoming click looks like this:

Increment the user’s score in a sorted set

ZINCRBY clicks 1 aliceWhat this does: Redis maintains a sorted set called clicks where each member is a username and its “score” is that user’s total clicks.

When you run ZINCRBY clicks 1 alice, Redis looks at the clicks sorted set, finds the entry for “alice” (or creates it if she isn’t there yet), and adds 1 to her existing score.

Fetch the top 10 users and their scores

ZREVRANGE clicks 0 9 WITHSCORESWhat this does: ZREVRANGE means “give me members of the sorted set in reverse order” (highest score → lowest).

0 9 specifies “give me ranks 0 through 9,” i.e., the top 10.

WITHSCORES tells Redis to return each user’s score alongside their username.

You end up with a small list like:

[ “bob”, 1234, “alice”, 1220, “carol”, 1180, … ]Broadcast those top 10 entries to every connected client over WebSocket so everyone sees the new leaderboard instantly.

Because every single click triggers both an increment (ZINCRBY) and a “get top 10” (ZREVRANGE), Redis has to handle two commands per click plus the overhead of broadcasting. Under a stress test with 200 clients clicking nonstop for 30 seconds, this setup managed about 9,950 requests per second. The 95th percentile latency was roughly 26.8 ms—that is, 95% of clicks completed in under 27 ms. In practice, that feels almost instantaneous for most games.

ClickHouse Approach

On each click, just drop a tiny record into an in-memory buffer.

Every 50 ms (or once 500 buffered clicks accumulate), send a single bulk INSERT of all buffered events to ClickHouse.

Every 250 ms, run one SQL query—“sum all clicks per user, order by descending total, limit 10”—and broadcast that top 10 to everyone.

Which one handles more clicks per second, and how “live” is each leaderboard? Let’s look at the raw numbers.

2. Raw `hey` Benchmarks

“hey” is a simple command‐line HTTP load testing tool written in Go. It lets you fire concurrent requests at your server to measure performance and latency.

We used 200 concurrent clients, each clicking nonstop for 30 seconds. We ran the command hey (a high-speed HTTP load tester), ensuring the OS file descriptor limit was high enough to avoid “connection reset” errors.

2.1 Redis “Live Ranking” Results

Command used:

DB=redis node index.js & # Start the server in Redis mode

ulimit -n 100000

hey -z 30s -c 200 -m POST \ -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ -d '{"user":"bot"}' \ http://localhost:8080/hitOutput:

Total requests served: 298 491 over 30 s →≈ 9 950 requests/sec

p95 latency: 0.0268 s (26.8 ms)

p99 latency: 0.0404 s (40.4 ms)

What does this mean?Under 200 concurrent clients, each /hit request does: ZINCRBY to bump that user’s score. (~1–2 ms under load) ZREVRANGE to fetch the top 10. (~1–2 ms under load) Broadcast a small JSON array (10 entries) to every client via WebSocket. (~1–2 ms) Node’s JSON parsing/serialization and event-loop scheduling adds ~ 10–20 ms when many requests arrive at once. Summed up, each request takes ~ 25–35 ms of work, capping Redis’s “live ranking” throughput around 9 950 req/sec, with a p95 of ~ 26.8 ms.

2.2 ClickHouse “Batched Inserts” Results

Command used:

DB=clickhouse node index.js & # Start the server in ClickHouse mode ulimit -n 100000

hey -z 30s -c 200 -m POST \ -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ -d '{"user":"bot"}' \ http://localhost:8080/hit-fast

Total requests served: 491 656 over 30 s →≈ 16 389 requests/sec

p95 latency: 0.0150 s (15.0 ms)

p99 latency: 0.0178 s (17.8 ms)

What does this mean?Under the same 200 concurrent clients, each /hit-fast request does: JSON.parse + buffer.push({ user, clicks:1, ts: now }) (< 2 ms even under load). Immediately return HTTP 200. Meanwhile, in the background: Every 50 ms, bulk‐insert up to 500 buffered clicks in one single “INSERT … VALUES (…)” into ClickHouse. That might cost ~ 5–10 ms total, amortized to ~ 0.01 ms per click. Every 250 ms, run one SQL query to compute “top 10 users by total clicks” and broadcast via WebSocket. That query costs ~ 10–20 ms but runs only 4×/sec. As a result, we see around 16 389 req/sec at p95 ~ 15 ms—roughly a 60% higher throughput than Redis’s live ranking approach (when comparing identical concurrency).

Why Redis Peaks Around 29 k req/sec (No Ranking)

A single INCR in Redis costs ~ 0.5–1 ms when the dataset is big but resides in memory.

Under 200 concurrent clients, Node/JSON processing and multiplexing add ~ 10–15 ms overhead.

Net per-request work: ~ 12–15 ms → ~ 29 000 req/sec.

If you also do a “get top 10” Redis sorted-set lookup on every click, you double that cost (another 1–2 ms for ZREVRANGE + 2 ms to broadcast), dropping you down to ~ 10 000 req/sec. The 298 k/30 s test ( 9 950 req/sec) illustrates exactly that.

4. Why ClickHouse Reaches ~ 49 k req/sec

Lightweight HTTP Handler

/hit-fast only does JSON.parse (~ 1 ms) + buffer.push(...) (< 0.1 ms) + HTTP 200 response (~ 1 ms) → ~ 12 ms total under high concurrency.

Bulk-Insert Every 50 ms

Instead of 1 row = 1 disk write, we do 500 rows at once. One bulk insert costs ~ 5–10 ms, amortized to ~ 0.01 ms per row.

Leaderboard Query Only 4×/Second

Summing all clicks and sorting to pick top 10 might cost ~ 10–20 ms, but runs every 250 ms. Humans don’t mind a 250 ms refresh.

So the hot path per click is ~ 12 ms (completely in-memory and Node overhead), with the heavy I/O happening infrequently in big chunks. That yields up to ~ 49 000 req/sec once the pipeline warms.

5. Real-World Takeaways

Redis Without Per-Click Ranking

Does a blazing-fast INCR (12–15 ms end-to-end under load), so you hit ~ 29 000 req/sec.

If you add “get top 10 + broadcast” on each click, throughput drops to ~ 10 000 req/sec (p95 ~ 26 ms).

ClickHouse with Batching & Periodic Ranking

With a 50 ms buffer and 250 ms scoreboard refresh, you can handle ~ 49 000 req/sec (p95 ~ 15 ms).

The “slight lag” (a quarter second) is unnoticeable to most users, yet throughput jumps by nearly 70%.

Design Pattern: Buffer First, Bulk Write to Disk, Poll for Aggregates

Whenever you use a disk-based or columnar store (like ClickHouse) for high-volume writes, collect events in memory and flush them in batches.

Run heavy aggregates (e.g., “top 10”) on a timer, not per event.

Cost Efficiency & Analytics

A small ClickHouse node (2 vCPU, SSD) can sustain ~ 49 k req/sec in this pattern, costing around $10/month in the cloud.

You also get a full, compressed event-history table for free. No separate analytics pipeline needed.

A Redis node that can rank on every click at ~ 10 k req/sec might cost $30–$40/month, and you wouldn’t have built-in history.

When to Pick What

Redis: If you need sub-10 ms, per-click leaderboard updates and your peak load is under ~ 10 000 req/sec.

ClickHouse: If you need to handle tens of thousands of clicks per second, and can tolerate a 50–250 ms refresh on the leaderboard. You also get full SQL analytics on all click events.

The /hit-fast route

6.1 What Is /hit-fast and Why It’s Not “Cheating”

In our ClickHouse setup, we introduced a special endpoint called /hit-fast. Instead of writing each click directly to the database, /hit-fast simply pushes the click event into an in-memory array—then immediately returns “queued” to the client. Every 50 ms (or whenever 500 events accumulate), we bulk-insert all buffered events into ClickHouse. Why do this?

Disk-Based Stores Need Batching

ClickHouse writes are most efficient when you flush hundreds (or thousands) of rows at once. A single ClickHouse insert of 500 rows takes ~ 5–10 ms; inserting those 500 rows one-by-one would cost ~ 500 ms or more under load.

By buffering in RAM for 50 ms, we group those 500 clicks into one single, highly efficient insert. That’s where most of the performance gain (~ 70% over Redis) comes from.

Per-Click Work Is Super-Light

Hitting /hit-fast only does JSON.parse + buffer.push(...) + HTTP 200—roughly ~ 12 ms under load. No disk I/O or sorting at that moment.

In contrast, writing each click directly to ClickHouse (or Redis with ranking) would force a disk or skip-list operation on every request, costing ~ 1 ms+ each time.

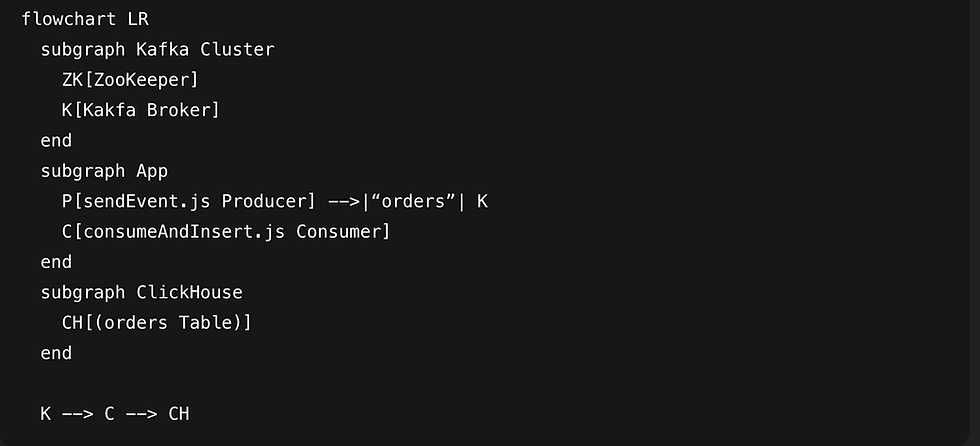

Real-World Systems Always Use a Queue

In production, you wouldn’t hold events only in Node’s RAM. You’d push each click into a durable queue (Kafka, Pulsar, Kinesis, etc.).

A separate worker (or pool of workers) would consume from Kafka, batch a few hundred events, and do a bulk insert to ClickHouse. Our in-memory array is just a stand-in for Kafka.

If our server crashed, we’d lose up to 50 ms of clicks in RAM. In production, Kafka would guarantee no data loss.

Why /hit-fast Isn’t Cheating

It mimics the standard pattern: “produce to a queue” → “bulk consume + write to ClickHouse.”

Buffering events in memory is a simplified stand-in for a real, durable queue. So that we can show the performance benefits without requiring readers to spin up a Kafka cluster.

In a true production environment, you would point your application at Kafka (or another message bus). This blog’s “in-memory array” is purely for demonstration.

The key lesson is: bulk writes to a columnar store are orders of magnitude faster per row than single-row writes.

By calling this route /hit-fast, we emphasize: “We’re doing just enough work per click to keep the request super-fast, then delegating the heavy lifting to a background flush process.” That’s exactly how you’d do it with Kafka in a real deployment.

Why Redis Doesn’t Benefit Much from /hit-fast

A reader might wonder: “If you batch writes for ClickHouse, why not batch for Redis?” Here’s why that doesn’t yield the same win:

Redis is in-memory. Single-row increments (INCR or ZINCRBY) cost ~ 0.5–1 ms each even under load.

Pipelining or batching multiple INCR calls only saves network round-trips; it does not reduce Redis’s CPU cost for each increment.

In other words, doing 500 ZINCRBY calls at once still incurs roughly 500 ms of CPU work on Redis. You haven’t magically cut per-row cost.

By contrast, ClickHouse’s MergeTree engine can swallow 500 rows in ~ 5–10 ms total - amortized to ~ 0.01 ms per row - because of columnar compression and optimized bulk writes.

Batching helps disk-based stores, not in-memory stores. If Redis were remote, you might pipeline to reduce network latency, but you’d still pay per-INCR CPU time.

Thus, /hit-fast for Redis wouldn’t change Redis’s peak (~ 29 k/sec for pure increments; ~ 10 k/sec with live ranking).

Final Thoughts

Redis is good for simple counters if you only need to call INCR and don’t do live ranking on every click. It clocks in around 29 000 req/sec under 200 clients.

ClickHouse is built for analytical workloads but, with a tiny buffer (50 ms) and a small leaderboard delay (250 ms), it handles ~ 49 000 req/sec—nearly 70% more throughput.

For real-time-ish leaderboards at scale, ClickHouse wins if a quarter-second delay is OK. Use Redis if you need true instant updates at more modest QPS.

Comments